Salil Chowdhury, fondly referred to as “Salil-da” was a music director, musician, writer, and poet, who worked in Hindi, Bengali, and the south Indian film industries. He was most active from the 1950’s through the 1960’s. His strength was in the fact that he mastered numerous different genre. He was accomplished on the flute, esraj, violin, and piano; he was also a master lyricist and writer. He is fondly remembered for some of the most famous songs to come out of Bollywood.

Salil Chowdhury was born on November 19, 1923 in the village of Sonarpur, in Bengal. He spent his early childhood in the Bengali village of Harinavi. However, his father was a doctor station in Assam, so he spent a lot of time there as well. Salil’s father had a collection of Western classical music, to which the young Salil spent much of his childhood listening. This was a musical influence which would be present through much of his life.

It was impressed upon the young Salil that ones art should maintain a sense of social responsibility. The fusion of art and politics was first presented to him by his father. His father used to take villagers and labourers and stage plays; these plays reflected the plight and social conditions of the times.

He attended the Bangabhaashi College in Calcutta. There his political interests grew. He became interested in the “Quit India” movement, as well as the general plight of the underclass. After he graduated from college, he joined the Communist Party of India, and became active in the Peasant Movement of 1945.

Shortly after his involvement in the Peasant Movement, he joined the Indian Peoples Theatre Association (IPTA). The purpose of this theatre was to raise the political consciousness of the common people. These theatres went from village to village and performed plays that revolved around the themes of British imperialism, various social iniquities, and the growing freedom struggle.

This forced Salil Chowdhury to go underground; for nearly four years he traveled around surreptitiously with the IPTA. Initially he joined as a flute player, but later he started to write songs. He lived among the peasants, and spent his time writing, composing, and performing. His works were by and large banned, so it was impossible to get any mainstream publisher to publish his plays or poetry. A large number of his works from this period have disappeared.

Life for the performers in the IPTA was very hard. Many were volunteers, but a few like Salil-da, received a small salary. They often traveled by foot, and sometimes went for days without food. If the police came to know that their troupe was performing, they would often arrive and start beating people indiscriminately. Many members died from torture, beating, and even starvation.

During his time with the IPTA, Salil Chowdhury distinguished himself by introducing a new approach to the music. The years of listening to his father’s Western classical music collection, gave him a feeling for Western concepts of harmony which were very different from traditional Indian music.

Ultimately he had a falling out with the IPTA. The reasons for his departure are varied, but they involve such factors as the infighting that was going on within the Communist party, petty personal jealousies over his success, as well as the Communist Party’s attempts to control the artistic content of his work.

A pivotal event occurred during this period of his life. He wrote a Bengali story called “Rikshawalla”. This was made into a Bengali movie which became a big hit. It was the success of this film that was to forever change Salil-da’s life.

Salil Chowdhury moved to Bombay in 1953 to adapt his Bengali “Rikshawalla” for Hindi; thus began his work in the Hindi film industry. This Hindi remake was entitled “Do Bigha Zameen”. The success of this movie ushered in a slew of other Hindi films. One of the most notable was Madhumati (1958).

Scene from Do Bigha Zameen

During the 50s; and 60s, Salil Chowdhury was kept very busy. In 1957 he and Ruma Ganguly, established the Bombay Youth Choir. This drew heavily upon Western concepts of harmony. Often he was the music director for films. He also composed background music for the documentaries which were coming out of the Films Division. Other times, music directors would hire him to do the background music while they would do the song-and-dance numbers. One example where he wrote the background music for another music director was “Anokhi Raat” (1968).

One of the things which characterised his way of working was that it was backwards from the establish norms of film production. The normal way of doing things was to first contact the lyricist, then take the lyrics to the music director who would set it to music. Salil-da would first compose the music and then set words to it. This high priority given to the music is often considered one of the reasons for the extraordinary quality of his music.

The Bollywood film industry is known for an extensive amount of “borrowing” of musical ideas from other sources. Like most of the other music directors, Salil Chowdhury has been accused of plagiarism due to his “borrowing” material from Western classical and traditional music. He has lifted material from a variety of sources from Mozart, to Happy Birthday To You.

There are numerous anecdotes about Salil-da. On one occasion he disappeared on route from Calcutta to Bombay. He was gone for several months, but eventually he shows up. Apparently he had spent time in some remote village to reacquaint himself with village life and village music.

The film world is known for its ego clashes and conflicts; Salil Chowdhury was no exception. There was a much publicised falling out that he had with Hemant Kumar (a.k.a. Hemanta Mukherjee). There was a time when their professional collaboration was very close. It is said the Salil Chowdhury once said, “If God ever decided to sing, he would do so in the voice of Hemant Kumar.” But things turned sour. According to a published obituary that Salil Chowdhury wrote on the death of Hemant Kumar:

“They went to Hemanta-da and complained ‘Salil Chowdhury is saying – “Hemanta Mukherjee would not have been popular if he had not sung my songs”‘. And the very same people came to me saying ‘Hemanta-da says – “If I had not sung Salil’s songs who would have know him today?”‘

The result of such games was very predictable. For some years they refused to work with each other. Eventually there was a reconciliation, but it appears that by that time, both Hemant and Salil were past their productive prime.

The mid 60’s saw Salil Chowdhuri in somewhat of a professional quagmire. It was not really going anywhere in Bombay and he was just not quite able to duplicate the success he had in Madhumati. He therefore started to work in the Malayali Cinema. He was very successful in this regard and over the next few years he scored what many believe are some of the finest songs that the Malayali cinema has ever heard. Some notable examples of this period are “Chemmeen” (1965).

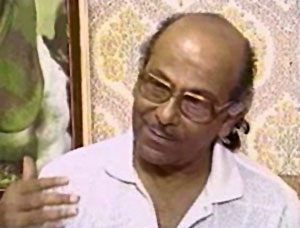

In the 1970’s Salil Chowdhury withdrew from the Hindi film world. Changing public tastes did not suite him. He returned to Calcutta. There he established the Centre for Music Research, and established a recording studio named “Sound on Sound”. He was involved in a number of minor projects in his later years.

Salil Chowdhuri circa 1978

In his waning years, Salil Chowdhury never lost the sense of social responsibility. He railed both in the press and privately against commercialism in the mainstream media and the lack of social consciousness. He also expressed great regret at the fragmentation of leftist movements both in and outside of India.

Salil Chowdhury passed away on Sept 5th, 1995. Among his survivors were his wife Sabita, his daughter Antara and sons Sanjoy and Bobby.